Leivits, M., Leivits, A., Klein, A., Kuus, A., Leibak, E., Merivee, M., Soppe, A., Tammekänd, I., Tammekänd, J. & Vilbaste, E.

Effects of visitor disturbance to the Golden Plover (Pluvialis apricaria) habitat suitability in Nigula bog

PDF

Ots, M.

Rarities in Estonia 2007-2008: Report of the Estonian Rarities Committee

Aua, J.

Nest site selection and nest predation in Eider (Somateria mollissima) on Kolga Bay islands

PDF

Notes

PDF

Chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Elts, J., Kuresoo, A., Leibak, E., Leito, A., Leivits, A., Lilleleht, V., Luigujõe, L., Mägi, E., Nellis, R., Nellis, R. & Ots, M.

Status and numbers of Estonian birds, 2003–2008

PDF

Ots, M.

White Stork in Estonia till 2008

PDF

Pehlak, H.

The oldest Southern Dunlin (Calidris alpina schinzii) known in Estonia was found breeding in Põgari

PDF

Aua, J.

Changes in winter flock size and sex ratio in Great Tit (Parus major)

PDF

Chronicle and news (in Estonian)

PDF

Pehlak, H.

Migration of the Broad-billed Sandpiper (Limicola falcinellus) in Estonia

PDF

Mägi, M.

Nest box birds in coniferous and deciduous forests surrounding Kilingi-Nõmme

PDF

Leito, A., Truu, J., Leito, T. & Põder, I.

Comparison of bird associations breeding in similar forest types on Hanikatsi islet and elsewhere Estonia.

PDF

Czechowski, P. & Zduniak, P.

Untypical eggs of the Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica)

PDF

Aua, J.

Structural changes in bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) winter flocks during early spring in 1999

PDF

Notes

PDF

Lõhmus, A. & Väli, Ü.

The journal Hirundo in the Estonian ornithology, 1988-2007

PDF

Mägi, E.

Bird species and nesting densities in reed-beds of West Estonian coast and Käina Bay

PDF

Marja, R.

Relationship between bird fauna diversity and landscape metrics in agricultural landscape: Estonian case study

PDF

Notes (in Estonian)

Elts, J. & Marja, R.

Counts of singing male corncrakes (Crex crex) in Karula National Park during 2003 and 2004 and the effect of song playbacks on counting efficiency

PDF

Ots, M. & Paal, U.

Rarities in Estonia 2005-2006: Report of the Estonian Rarities Committee

Summary: This sixth report of the Estonian Rarities Committee covers the years 2005-2006, but some earlier records have also been included. Altogether 168 records were definitely assessed (Table 1), and 156 (93%) of these were accepted.

The records are listed in systematic order and presented chronologically. Records of birds of unclear origin, escapees from captivity, corrections and changes, records not accepted, and records formerly accepted but now rejected are listed separately from the main list of accepted records. The four numbers in brackets after species’ name (a/b – c/d) indicate (a) the total number of records before 2005, (b) the number of individuals (if possible to judge) before 2005; © the number of records in 2005-2006, (d) the number of individuals in 2005-2006. X instead of a number means unknown number of records or individuals. The details included for each record are: date(s), locality, parish (khk.), district, number of individuals (is., isend), pairs (paar), nests (pesa) etc. if more than one, sex and age (if known; a = calendar year) and name(s) of observer(s). The meaning of some Estonian terms and expressions: ja = and, läh. = near, vahel = between, jv. = lake, s. = island, laht = bay, (tõenäoliselt) sama isend = (probably) the same individual, pesitsemine = breeding. In (2004) 2005-2006, 9 new species in an apparently wild state (AERC category A) were added to Estonian list: in 2004 Stercorarius skua, in 2005 Egretta garzetta, Porzana pusilla, Calidris melanotos, Larus glaucoides, Prunella collaris and Sylvia nana, in 2006 Falco naumanni and Tryngites subruficollis. Altogether, 360 species of apparently wild state or released species which have established self-supporting breeding populations in Estonia or in neighbouring countries (i.e. categories A-C) and 5 species of unclear origin (category D) have been recorded in Estonia by 31.12.2006.

Aua, J.

Belated lapwings (Vanellus vanellus)

PDF

Sellis, U., Männik, R. & Väli, Ü.

*Maria on migration: a satellite-telemetrical study on spring and autumn migration of an Estonian

osprey (Pandion haliaetus)*

PDF

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Lõhmus, A.

Nesting ecology of birds of prey and owls near Saue, 1959–2006

PDF

Metsaorg, L., Allemann, M. & Peterson, K.

Notes on the breeding avifauna of the islets of Eru bay from 1986-2005

PDF

Notes

Aua, J.

Food storaging behaviour by a rook (Corvus frugilegus).

Kinks, R.

A nest of hoopoe (Upupa epops) found in Lääne-Virumaa

PDF

Chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Erit, M.

The importance of the Silma Nature Reserve for birds breeding in meadows and reed-beds

Abstract: The aim of current study was to determine the role and level of importance of the Silma Nature Reserve (NR) for the birds, who prefer meadows and reed beds as their breeding habitat. To determine species and numbers of avifauna in Silma NR, breeding pairs in selected model areas were counted and this data was extrapolated on whole area of the NR. For less abundant species the effort was made to count all breeding pairs in the whole area. In total, abundance of 50 breeding species in was recorded. In the case of 17 species over 1% of total population in Estonia was represented in studied area. More than 5% of the total Estonian populations of bearded tits (Panurus biarmicus; 16,7%), greylag geese (Anser anser; 8,4%), mute swans (Cygnus olor; 6,5%), Savi’s warblers (Locustella luscinioides; 5,9%) and great reed warblers (Acrocephalus arundinaceus; 5,2%) breed in Silma NR.

Sein,G. & Lõhmus, A.

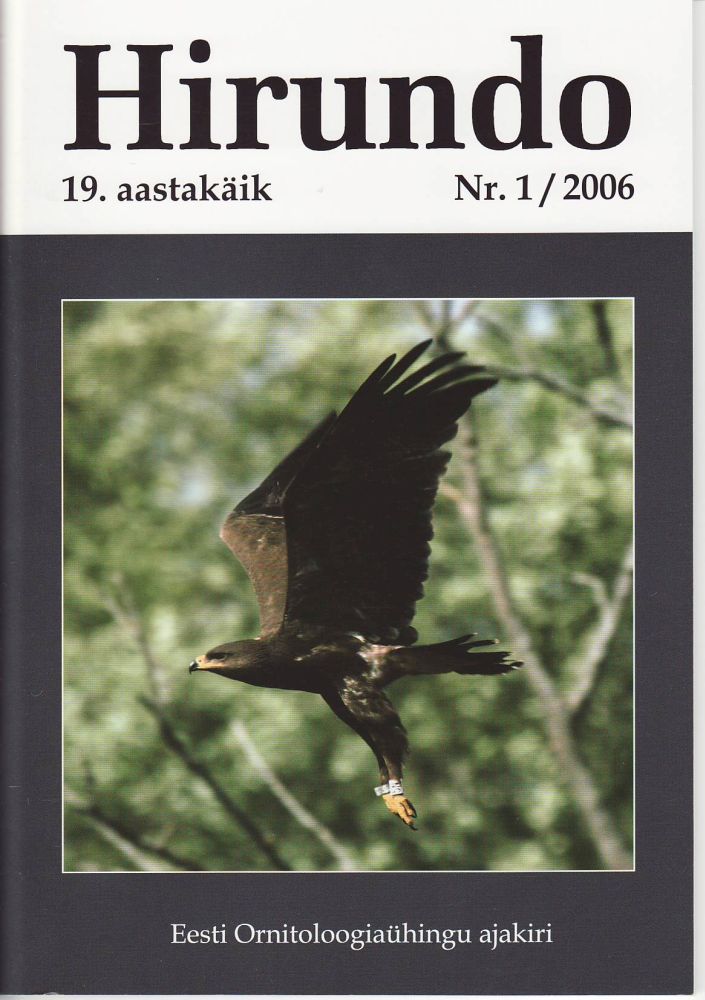

Nest-stand and nest-tree characteristics of the Golden eagle in Estonia

Abstract: Nest-site use by the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) has not been studied in Estonia in detail before. This paper, based on nest-sites occupied in 1995–2004, (1) describes the eagle’s nest trees, their

surrounding forest stands and location on the landscape; (2) compares nest trees with average trees available around; and (3) explores the potential relationships between the location and nesting success of the eagle. The average tree composition of 21 nest stands comprised 49% Scots pine, 29% Norway spruce, 14% birch, 7% aspen, 1% black alder and 1% grey alder. Fifteen nests (71%) were built on pine, four on spruce and two on aspen. The average age of nest-trees was 142 (quartile range 130–155) years and the average diameter was 48 (41–51) cm. Amongst the available trees in the nest-stand, Golden Eagles selected nest-trees that were on average 35 years older and 19 cm thicker (16 cm in case of pines), which can be explained with the better nest-building opportunities in such trees. There was no such difference in tree heights. The closest forest edge was situated on average 56 m, road 1.8 km, and house 2.8 km from the nest; distances to the nearest occupied nest of another Golden Eagle and of the White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) were 10 km and 2.8 km, respectively. No significant relationships were found between nest location on the landscape and breeding success there, but the analysis lacked power due to small samples and short time‐frame (breeding success could be only established as the average for two years in each nest).

Nellis, R.

Goshawk – bird of the year 2005

Drevs, T. & Jürgens, M.

Some observations on the nest-site preferences of the Merlin in Tallinn area

Notes (in Estonian)

Nellis, R. Nutcracker (Nucifraga caryocatactes) attacking a mouse

Elts, J. & Marja, R. A Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) nestling in Jackdaw’s (Corvus monedula) diet

EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Väli, Ü. & Laurits, M.

The composition and breeding density of forest birds in Kõpu nature reserve (Western Hiiumaa)

PDF

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Puumets, R.

Bird fauna of Paljassaare peninsula in Tallinn

PDF

Uustal, M. & Peterson, K.

Changes in the bird fauna of Tallinn from 1900 to 2005

PDF Electronic appendix

Notes (in Estonian)

Elts, J. Feeding habits of fieldfare (Turdus pilaris) in especially cold weather conditions

Bird Conservation News (in Estonian)

Colour ringing of Estonian spotted eagles (Aquila pomarina et clanga) started

EOS chronicle (in Estonian)

Ellermaa, M.

Breeding densities of common breeding species in managed mixed and moist forests in Pärnumaa, Estonia

PDF

Ots, M. & Klein, A.

Rarities in Estonia 2003-2004: Report of the Estonian Rarities Committee

Summary: This fifth report of the Estonian Rarities Committee covers the years 2003-2004, but some earlier records have also been included. Altogether 214 records were definitely assessed (Table 1), and 192 (90%) of these were accepted. The records are listed in systematic order (according to the new recommendations of AERC) and presented chronologically. Records of birds of unclear origin, escapees from captivity, corrections and changes, records not accepted, and records formerly accepted but now rejected are listed separately from the main list of accepted records. The four numbers in brackets after species’ name (a/b – c/d) indicate (a) the total number of records before 2003, (b) the number of individuals (if possible to judge) before 2003; © the number of records in 2003-2004, (d) the number of individuals in 2003-2004. X instead of a number means unknown number of records or individuals. The details included for each record are: date(s), locality, parish (khk.), district, number of individuals (is., isend), pairs (♂♀), nests (pesa) etc. if more than one, sex and age (if known; a = calendar year) and names of observers. The meaning of some Estonian terms and expressions: ja = and, läh. = near, jv. = lake, s. = island, laht = bay, (tõenäoliselt) sama isend = (probably) the same individual, pesitsemine = breeding. In 2003-2004, 6 new species in an apparently wild state (AERC category A) were added to the Estonian list: in 2003 Anas carolinensis, Calonectris diomedea and Emberiza melanocephala, in 2004 Hirundo daurica, Oenanthe pleschanka and Hippolais pallida. The race Motacilla alba yarrellii was recorded for the first time in Estonia in 1997 but accepted during the reporting period. Also one species of unclear origin (category D) – Lophodytes cucullatus and two species of category E (escapees from captivity) – Anser rossii and Anas cyanoptera – were recorded for the first time in 2003 in Estonia. In the same period, the breeding of Ficedula albicollis in Estonia was confirmed. Altogether, 350 species of apparently wild state or released species which have established self-supporting breeding populations in Estonia or in neighbouring countries (i.e. categories A-C) and 6 species of unclear origin (category D) have been recorded in Estonia by 31.12.2005

Notes (in Estonian)

Jürgens, M. On the vocal mimetic ability of common redstart

Ellermaa, M. Some observations of albinistic and melanistic birds

Bird conservation news, EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Elts, J.

Numbers and population dynamics of the Common Sandpiper in the surroundings of Saue, 1963-2003

PDF

Väli, Ü.

Habitat use of the Red-backed Shrike in Estonia

PDF

Lõhmus, A. & Rosenvald, R.

Breeding bird fauna of the Järvselja Primeval Forest Reserve: long-term changes and an analysis of inventory methods

Summary: The Järvselja Primeval Forest Reserve (19 ha) in eastern Estonia (58°17’N, 27°19’E) was established in 1924. It contains three main forest types: mixed or broad-leaved nemoral forest (6.2 ha), Alnus glutinosa swamp forest (2.7 ha) and drained peatland forest of Pinus sylvestris (10.1 ha; Fig. 1). The area has been probably never cleared, but it is surrounded by drainage ditches. Previously, its breeding birds have been censused in 1973 and 1982 (Karoles 1975, Rootsmäe & Rootsmäe 1993).

In 2005, we mapped breeding birds in the reserve between 10 May and 17 June during seven mornings and three other visits. The aims were (1) to compare the situation with the previous censuses; (2) to check the reliability of a two-day inventory, which included a standard morning count and a later visit during the day on 10 and 31 May. Results of the inventory (maximum counts of each species) were compared with those of the standard mapping, based on two-record clusters and a careful analysis of simultaneous observations.

172 pairs of 35 species were detected (9.1 pairs ha-1). The total number of species (34-36) and of pairs (9.1-10.1 pairs ha-1) have been very stable in the three censuses (1973, 1982, 2005), though large differences appear for individual species (Table 1). These differences may be partly due to methodological aspects and annual fluctuations, but some trends may be also related to the forest dynamics in the reserve: (1) abundance of very old or dead spruces – increases of Picoides tridactylus, Certhia familiaris, Parus ater; (2) disappearance of old hollow aspens – decreases of Columba oenas, Ficedula hypoleuca, Sitta europaea; (3) overgrowth of the drained pine forest with spruce – loss of Anthus trivialis and Muscicapa striata.

In larger (>6 ha) plots, the two-day inventory resulted in c. 40% underestimation of numbers and missing of rare species; Shannon’s (but not Simpson’s) index of species diversity was almost accurate (Table 2). In the narrow and small swamp forest, many birds from the surroundings were also recorded, so this plot seemed more diverse than it actually was. We conclude that short-term inventories can be used for comparing the density and diversity in >5-ha plots; the estimation of absolute densities requires assessments of the underestimation bias.

Elts, J.

On the nest material of the Willow Warbler: a quantitative analysis

PDF

Elts, J. & Kuus, A.

The new Estonian atlas of breeding birds: results of the first study year

Summary: In 2004, compilation of the new breeding bird atlas started in Estonia. The country is divided into 2094 5×5 km-squares. Altogether 391 persons joined to project in the first study year, and up to now we have received data from 584 squares. In maximum, 122 breeding species has been observed in a square.

Mänd, R.

Benchmarks of the Estonian academic ornithology in the new independence period

Summary: During the new independence period, altogether six PhD theses have been completed by Estonian ornithologists (Peeter Hõrak, Indrek Ots, Vallo Tilgar, Asko Lõhmus, Ülo Väli, Lauri Saks), which constitutes about 6% of all doctoral dissertations in bio-geosciences during that period in Estonia. These works mostly deal with the acute problems of ecophysiology, life history evolution, sexual selection and conservation biology of birds.

‘Notes (in Estonian)*

Paal, U. Rare wintering birds in Estonia 2004/2005

Kalamees, A. & Elts, J. A Goshawk flying 70 km/h

Aun, S. & Aun, E. Water struggle between a Goshawk and a Goldeneye

Vohta, T. A Marsh Harrier attacked a Grey Heron

Sellis, U. A Marsh Harrier caught a fish

Vohta, T. A Raven helped a dog to catch a hare

Väli, Ü. An Oystercatcher bred on the roadside

Väli, Ü. On the feeding of Grey-headed Woodpecker nestlings

EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)