Elts, J. & Marja, R.

Counts of singing male corncrakes (Crex crex) in Karula National Park during 2003 and 2004 and the effect of song playbacks on counting efficiency

PDF

Ots, M. & Paal, U.

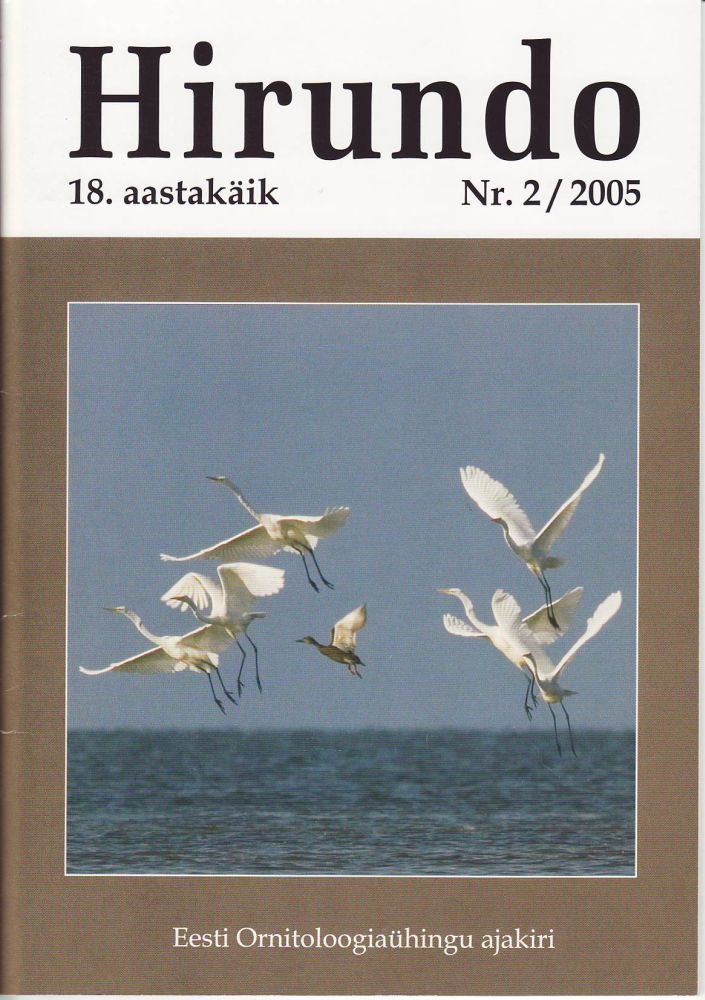

Rarities in Estonia 2005-2006: Report of the Estonian Rarities Committee

Summary: This sixth report of the Estonian Rarities Committee covers the years 2005-2006, but some earlier records have also been included. Altogether 168 records were definitely assessed (Table 1), and 156 (93%) of these were accepted.

The records are listed in systematic order and presented chronologically. Records of birds of unclear origin, escapees from captivity, corrections and changes, records not accepted, and records formerly accepted but now rejected are listed separately from the main list of accepted records. The four numbers in brackets after species’ name (a/b – c/d) indicate (a) the total number of records before 2005, (b) the number of individuals (if possible to judge) before 2005; © the number of records in 2005-2006, (d) the number of individuals in 2005-2006. X instead of a number means unknown number of records or individuals. The details included for each record are: date(s), locality, parish (khk.), district, number of individuals (is., isend), pairs (paar), nests (pesa) etc. if more than one, sex and age (if known; a = calendar year) and name(s) of observer(s). The meaning of some Estonian terms and expressions: ja = and, läh. = near, vahel = between, jv. = lake, s. = island, laht = bay, (tõenäoliselt) sama isend = (probably) the same individual, pesitsemine = breeding. In (2004) 2005-2006, 9 new species in an apparently wild state (AERC category A) were added to Estonian list: in 2004 Stercorarius skua, in 2005 Egretta garzetta, Porzana pusilla, Calidris melanotos, Larus glaucoides, Prunella collaris and Sylvia nana, in 2006 Falco naumanni and Tryngites subruficollis. Altogether, 360 species of apparently wild state or released species which have established self-supporting breeding populations in Estonia or in neighbouring countries (i.e. categories A-C) and 5 species of unclear origin (category D) have been recorded in Estonia by 31.12.2006.

Aua, J.

Belated lapwings (Vanellus vanellus)

PDF

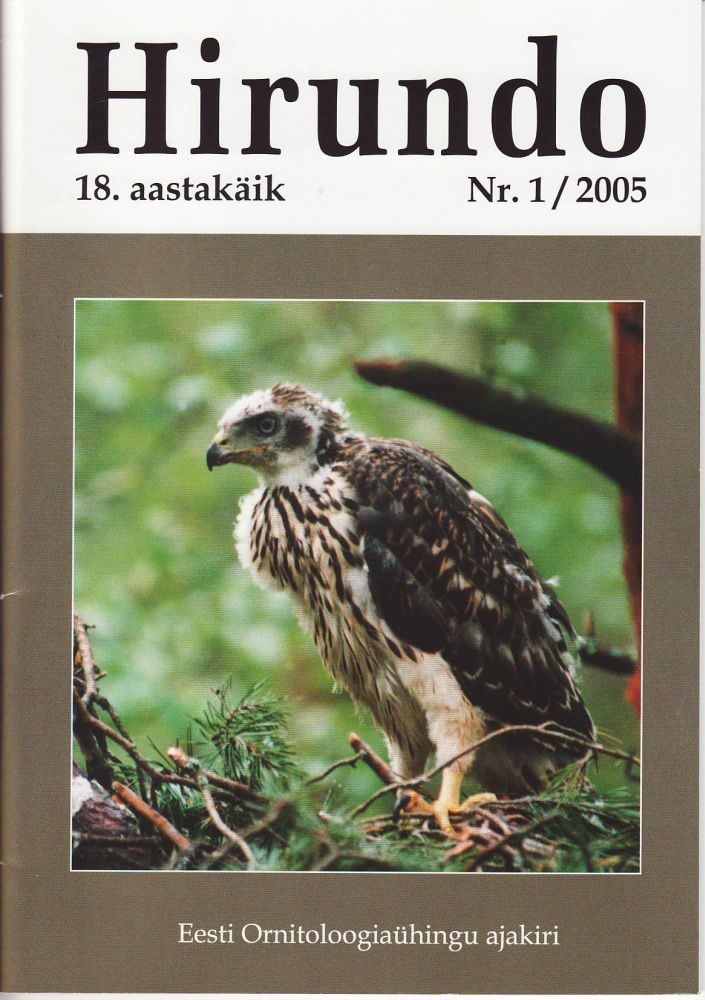

Sellis, U., Männik, R. & Väli, Ü.

*Maria on migration: a satellite-telemetrical study on spring and autumn migration of an Estonian

osprey (Pandion haliaetus)*

PDF

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Lõhmus, A.

Nesting ecology of birds of prey and owls near Saue, 1959–2006

PDF

Metsaorg, L., Allemann, M. & Peterson, K.

Notes on the breeding avifauna of the islets of Eru bay from 1986-2005

PDF

Notes

Aua, J.

Food storaging behaviour by a rook (Corvus frugilegus).

Kinks, R.

A nest of hoopoe (Upupa epops) found in Lääne-Virumaa

PDF

Chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Erit, M.

The importance of the Silma Nature Reserve for birds breeding in meadows and reed-beds

Abstract: The aim of current study was to determine the role and level of importance of the Silma Nature Reserve (NR) for the birds, who prefer meadows and reed beds as their breeding habitat. To determine species and numbers of avifauna in Silma NR, breeding pairs in selected model areas were counted and this data was extrapolated on whole area of the NR. For less abundant species the effort was made to count all breeding pairs in the whole area. In total, abundance of 50 breeding species in was recorded. In the case of 17 species over 1% of total population in Estonia was represented in studied area. More than 5% of the total Estonian populations of bearded tits (Panurus biarmicus; 16,7%), greylag geese (Anser anser; 8,4%), mute swans (Cygnus olor; 6,5%), Savi’s warblers (Locustella luscinioides; 5,9%) and great reed warblers (Acrocephalus arundinaceus; 5,2%) breed in Silma NR.

Sein,G. & Lõhmus, A.

Nest-stand and nest-tree characteristics of the Golden eagle in Estonia

Abstract: Nest-site use by the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) has not been studied in Estonia in detail before. This paper, based on nest-sites occupied in 1995–2004, (1) describes the eagle’s nest trees, their

surrounding forest stands and location on the landscape; (2) compares nest trees with average trees available around; and (3) explores the potential relationships between the location and nesting success of the eagle. The average tree composition of 21 nest stands comprised 49% Scots pine, 29% Norway spruce, 14% birch, 7% aspen, 1% black alder and 1% grey alder. Fifteen nests (71%) were built on pine, four on spruce and two on aspen. The average age of nest-trees was 142 (quartile range 130–155) years and the average diameter was 48 (41–51) cm. Amongst the available trees in the nest-stand, Golden Eagles selected nest-trees that were on average 35 years older and 19 cm thicker (16 cm in case of pines), which can be explained with the better nest-building opportunities in such trees. There was no such difference in tree heights. The closest forest edge was situated on average 56 m, road 1.8 km, and house 2.8 km from the nest; distances to the nearest occupied nest of another Golden Eagle and of the White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) were 10 km and 2.8 km, respectively. No significant relationships were found between nest location on the landscape and breeding success there, but the analysis lacked power due to small samples and short time‐frame (breeding success could be only established as the average for two years in each nest).

Nellis, R.

Goshawk – bird of the year 2005

Drevs, T. & Jürgens, M.

Some observations on the nest-site preferences of the Merlin in Tallinn area

Notes (in Estonian)

Nellis, R. Nutcracker (Nucifraga caryocatactes) attacking a mouse

Elts, J. & Marja, R. A Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) nestling in Jackdaw’s (Corvus monedula) diet

EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Väli, Ü. & Laurits, M.

The composition and breeding density of forest birds in Kõpu nature reserve (Western Hiiumaa)

PDF

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Puumets, R.

Bird fauna of Paljassaare peninsula in Tallinn

PDF

Uustal, M. & Peterson, K.

Changes in the bird fauna of Tallinn from 1900 to 2005

PDF Electronic appendix

Notes (in Estonian)

Elts, J. Feeding habits of fieldfare (Turdus pilaris) in especially cold weather conditions

Bird Conservation News (in Estonian)

Colour ringing of Estonian spotted eagles (Aquila pomarina et clanga) started

EOS chronicle (in Estonian)

Ellermaa, M.

Breeding densities of common breeding species in managed mixed and moist forests in Pärnumaa, Estonia

PDF

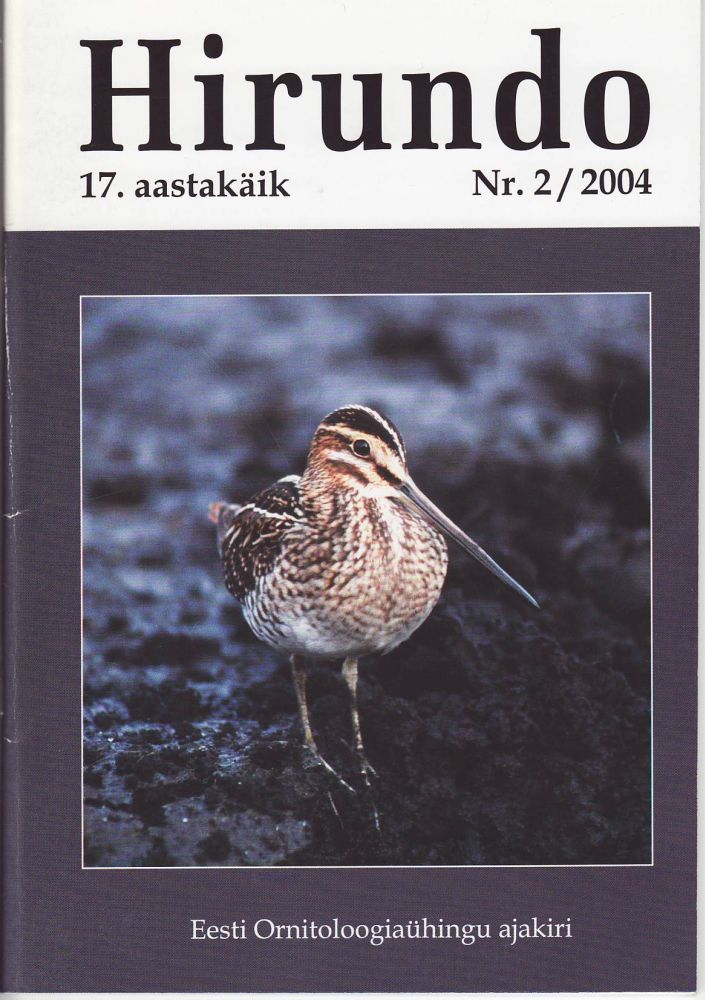

Ots, M. & Klein, A.

Rarities in Estonia 2003-2004: Report of the Estonian Rarities Committee

Summary: This fifth report of the Estonian Rarities Committee covers the years 2003-2004, but some earlier records have also been included. Altogether 214 records were definitely assessed (Table 1), and 192 (90%) of these were accepted. The records are listed in systematic order (according to the new recommendations of AERC) and presented chronologically. Records of birds of unclear origin, escapees from captivity, corrections and changes, records not accepted, and records formerly accepted but now rejected are listed separately from the main list of accepted records. The four numbers in brackets after species’ name (a/b – c/d) indicate (a) the total number of records before 2003, (b) the number of individuals (if possible to judge) before 2003; © the number of records in 2003-2004, (d) the number of individuals in 2003-2004. X instead of a number means unknown number of records or individuals. The details included for each record are: date(s), locality, parish (khk.), district, number of individuals (is., isend), pairs (♂♀), nests (pesa) etc. if more than one, sex and age (if known; a = calendar year) and names of observers. The meaning of some Estonian terms and expressions: ja = and, läh. = near, jv. = lake, s. = island, laht = bay, (tõenäoliselt) sama isend = (probably) the same individual, pesitsemine = breeding. In 2003-2004, 6 new species in an apparently wild state (AERC category A) were added to the Estonian list: in 2003 Anas carolinensis, Calonectris diomedea and Emberiza melanocephala, in 2004 Hirundo daurica, Oenanthe pleschanka and Hippolais pallida. The race Motacilla alba yarrellii was recorded for the first time in Estonia in 1997 but accepted during the reporting period. Also one species of unclear origin (category D) – Lophodytes cucullatus and two species of category E (escapees from captivity) – Anser rossii and Anas cyanoptera – were recorded for the first time in 2003 in Estonia. In the same period, the breeding of Ficedula albicollis in Estonia was confirmed. Altogether, 350 species of apparently wild state or released species which have established self-supporting breeding populations in Estonia or in neighbouring countries (i.e. categories A-C) and 6 species of unclear origin (category D) have been recorded in Estonia by 31.12.2005

Notes (in Estonian)

Jürgens, M. On the vocal mimetic ability of common redstart

Ellermaa, M. Some observations of albinistic and melanistic birds

Bird conservation news, EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Elts, J.

Numbers and population dynamics of the Common Sandpiper in the surroundings of Saue, 1963-2003

PDF

Väli, Ü.

Habitat use of the Red-backed Shrike in Estonia

PDF

Lõhmus, A. & Rosenvald, R.

Breeding bird fauna of the Järvselja Primeval Forest Reserve: long-term changes and an analysis of inventory methods

Summary: The Järvselja Primeval Forest Reserve (19 ha) in eastern Estonia (58°17’N, 27°19’E) was established in 1924. It contains three main forest types: mixed or broad-leaved nemoral forest (6.2 ha), Alnus glutinosa swamp forest (2.7 ha) and drained peatland forest of Pinus sylvestris (10.1 ha; Fig. 1). The area has been probably never cleared, but it is surrounded by drainage ditches. Previously, its breeding birds have been censused in 1973 and 1982 (Karoles 1975, Rootsmäe & Rootsmäe 1993).

In 2005, we mapped breeding birds in the reserve between 10 May and 17 June during seven mornings and three other visits. The aims were (1) to compare the situation with the previous censuses; (2) to check the reliability of a two-day inventory, which included a standard morning count and a later visit during the day on 10 and 31 May. Results of the inventory (maximum counts of each species) were compared with those of the standard mapping, based on two-record clusters and a careful analysis of simultaneous observations.

172 pairs of 35 species were detected (9.1 pairs ha-1). The total number of species (34-36) and of pairs (9.1-10.1 pairs ha-1) have been very stable in the three censuses (1973, 1982, 2005), though large differences appear for individual species (Table 1). These differences may be partly due to methodological aspects and annual fluctuations, but some trends may be also related to the forest dynamics in the reserve: (1) abundance of very old or dead spruces – increases of Picoides tridactylus, Certhia familiaris, Parus ater; (2) disappearance of old hollow aspens – decreases of Columba oenas, Ficedula hypoleuca, Sitta europaea; (3) overgrowth of the drained pine forest with spruce – loss of Anthus trivialis and Muscicapa striata.

In larger (>6 ha) plots, the two-day inventory resulted in c. 40% underestimation of numbers and missing of rare species; Shannon’s (but not Simpson’s) index of species diversity was almost accurate (Table 2). In the narrow and small swamp forest, many birds from the surroundings were also recorded, so this plot seemed more diverse than it actually was. We conclude that short-term inventories can be used for comparing the density and diversity in >5-ha plots; the estimation of absolute densities requires assessments of the underestimation bias.

Elts, J.

On the nest material of the Willow Warbler: a quantitative analysis

PDF

Elts, J. & Kuus, A.

The new Estonian atlas of breeding birds: results of the first study year

Summary: In 2004, compilation of the new breeding bird atlas started in Estonia. The country is divided into 2094 5×5 km-squares. Altogether 391 persons joined to project in the first study year, and up to now we have received data from 584 squares. In maximum, 122 breeding species has been observed in a square.

Mänd, R.

Benchmarks of the Estonian academic ornithology in the new independence period

Summary: During the new independence period, altogether six PhD theses have been completed by Estonian ornithologists (Peeter Hõrak, Indrek Ots, Vallo Tilgar, Asko Lõhmus, Ülo Väli, Lauri Saks), which constitutes about 6% of all doctoral dissertations in bio-geosciences during that period in Estonia. These works mostly deal with the acute problems of ecophysiology, life history evolution, sexual selection and conservation biology of birds.

‘Notes (in Estonian)*

Paal, U. Rare wintering birds in Estonia 2004/2005

Kalamees, A. & Elts, J. A Goshawk flying 70 km/h

Aun, S. & Aun, E. Water struggle between a Goshawk and a Goldeneye

Vohta, T. A Marsh Harrier attacked a Grey Heron

Sellis, U. A Marsh Harrier caught a fish

Vohta, T. A Raven helped a dog to catch a hare

Väli, Ü. An Oystercatcher bred on the roadside

Väli, Ü. On the feeding of Grey-headed Woodpecker nestlings

EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Lõhmus, A.

Causes of death of raptors and owls in Estonia, 1985-2004

Summary: Mortality of raptors and owls has not been specifically studied in Estonia (but see Randla & Tammur 1996b; Lõhmus 1994a, 2001, for data on some species) and this paper summarizes their causes of death in 1985-2004. The material has been collected all over the country (Fig. 1) by (1) the participants of national monitoring projects; (2) two wildlife-rehabilitation centres; (3) ecologists studying raptor diets and population ecology. The causes of death of full-grown birds were classified into 20 categories of four main types (Table 1); for nestlings, some additional categories were used. Yet, the frequencies of disease, poisoning and exhaustion are obviously underestimated, since autopsies have been seldom made and other proximate causes (traffic, predation) may have concealed the ultimate ones.

Most deaths of full-grown birds (n = 615; Tables 3-4) were directly or indirectly caused by man (47%; notably traffic, powerlines and other collisions and injuries) and predators (34%; mostly the Goshawk, Golden Eagle and Eagle Owl). The frequency distributions of causes of death did not differ significantly between first-year juveniles and older birds, which implies that mortality-reduction measures could be roughly the same for both age groups. In winter, the main causes of death for owls (n = 27) were traffic (15) and exhaustion (7); no specific causes dominated for raptors (n = 17).

An intensive study in northwestern Tartumaa revealed manyfold overestimation of the frequency of man-induced mortality among smaller species and Goshawks in the remaining material. Considering this bias, I suggest that antropogenic deaths are particularly important for eagles, the Osprey and the Eagle Owl, and possibly for the Goshawk and the Tawny Owl in Estonia. There were 27 cases of persecution (44% of these were eagles or the Osprey). In general, however, persecution is not likely to influence the Estonian raptor and owl populations significantly any more (probably, some tens of full-grown raptors and a few nestlings are killed annually).

The death of nestlings (n = 128) was mostly related to food shortage and disease (46%, incl. cannibalism) or nest predation (30%); in tree-nesting species, nestlings often fell down from the nest (19%).

In general, natural causes of death were more frequent in Estonia than in most other European countries, and no alarming trends for conservation were detected.

Erit, M.

How many counts are needed for efficient bird census on floodplain meadows?

Summary: Mapping of breeders’ territories (see Koskimies & Väisänen 1991, Gilbert et al. 1998, Bibby et al. 2000) is often used for censusing birds. Usually, mapping is based only on 2-3 counts, but the efficiency of such a small number of counts is unknown. In 2001-2003, breeding birds were mapped on floodplain meadows of River Emajõgi in the Alam-Pedja Nature Reserve. Territorial birds and ducks were mapped on two study plots seven (or eight) times per season (including 1-2 night counts). The aim of the current study was to estimate the apparent visit efficiency (ratio between the results obtained from a single count and all counts; Svensson 1978) of 1-4 morning counts compared to counts performed five times, and to find a minimum number of counts for correct estimation of breeding territories. In 5-visit counts, breeding pair was defined as a cluster formed of at least two observations. In ducks Anas sp., maximum number of individuals (excl. nonbreeding individuals in flocks) per count was considered as the number of breeding pairs.

Four species or species groups (table 1) were included to analysis. To estimate apparent visit efficiency, I used all possible combinations of counts from six datasets (two study plots, three years). The abundance, relative to 5-times-counts, was calculated using species maps. Average apparent visit efficiency for all breeding birds was 55% (SD 14%) for a single count, 80% (11%) for double counts and 97% (9%) for 3-visit counts (Figure 1). For 4-visit-counts, the efficiency was 109% (8%) if all registered territories were considered, and 83% (7%), if territory was defined by at least two observations. The efficiency of counts increased and their variance decreased significantly along with growing number of counts. Efficiency was smallest and most variable in non-passerines, especially in ducks. In three cases, I was able to analyse the efficiency of 5- compared with 6-visit counts, the efficiency was 90% (SD 4%). In the Common Snipe and Sedge Warbler, efficiency of single and double counts in their main breeding time was 7-10% higher than the average efficiency, but the variation did not differ significantly.

Consequently, birds of floodplain meadows should be mapped at least three times during a breeding season. Four counts per season gives more precise estimates if all observation clusters are defined as breeding territories, whatever the number of observations is. To estimate the numbers of particular species, two counts during the time of species’ maximum activity may be sufficient. When one is interested in the numbers of all birds breeding on a floodplain, the census should include also night counts.

Laurits, M., Erit, M., Kuresoo, A. & Luigujõe, L.

Is it necessary to describe vegetation composition and structure while mapping birds on floodplain meadows?

Summary: We analysed distribution of bird species on a floodplain meadow in relation to 1) general landscape structure elements (at microhabitat scale) and 2) vegetation type, which distinguishes vegetation associations by species composition and vegetation structure. By comparing the two approaches, we looked for an optimal method to follow bird-habitat relationships in bird monitoring.

Breeding birds were mapped according to Koskimies & Väisänen (1991) in a floodplain meadow of River Emajõgi in the Alam-Pedja Nature Reserve in 2001-2003. Seven counts (including two at night) were performed in 2001 and 2003, and five counts (incl. one at night) in 2002. During the counts, we described also the landscape elements (Table 1), where individual birds were recorded. Vegetation types (Table 2) were mapped in 2001; later only substantial changes were recorded.

Using the general approach, non-passerines and open-landscape passerines were distinguished as sedge-preferring (open floodplain) birds, but occurence of bushes or reedbed patches was important too (Table 1). The number of bird species and breeding density was higher in diverse areas. The detailed analysis of vegetation types distinguished the same taxa (Table 2), but enabled to determine the preference in more detail (vegetation density, height and lush, soil humidity).

Consequently, the two approaches gave similar results on relationships between birds and the vegetation, although the detailed vegetation mapping was more informative. Considering the increased cost of time and labour of the latter approach, we suggest to describe the basic structure of habitat as well as soil moisture during bird mapping.

Eenpuu, R. & Elts, J.

Invasion of the Fieldfare to Estonia in winter 2002/03

Summary: The overview of a Fieldfare Turdus pilaris invasion to Estonia in winter 2002/03 is based on ornithophenological data collected by the members of the Estonian Ornithological Society. In autumn 2002, rowanberries were extremely abundant. Invasion of fieldfares started in the last decade of November and lasted till the beginning of March. Largest flocks (up to 2500 birds) were seen in January and in the first half of February (Figure 1). According to the monitoring of winter land birds in Estonia, the 2002/03 invasion was the largest during the last decades (Figure 2). The numbers of breeding Fieldfares did not increase in 2003.

Lilleleht, V.

Changes in avian systematics

Summary: The article reviews the latest proposals in avian systematics, and the attempts of the Association of European Records and Rarities Committees (AERC) to standardise their implementation in Europe. The Estonian Rarities Committee (at the Estonian Ornithological Society), decided at 26.02.2004 to follow the recommendations of AERC also in the list of Estonian birds. The new Estonian list is available at www.eoy.ee

EOS chronicle and news (in Estonian)

Lõhmus, A.

Monitoring raptors and owls in Estonia, 1999-2003: decline of the Goshawk and the Clockwork of vole-cycles

Summary: The paper is the third summary of the raptor monitoring project of the Estonian Ornithological Society (see Lõhmus 1994, 1999a for previous reports). Nesting territories (NT) of raptors and owls were mapped in 19 study plots covering a total of 1870 km2 in 1999-2003 (Fig. 1). Land cover of the plots resembled the Estonian average situation (Table 1), hence the densities of evenly distributed species can be extrapolated to the whole country (Table 2). Potential nest sites were checked in three additional areas and also outside the plots; altogether 1889 occupied nests (the rare eagle species excluded) and 1540 brood sizes were recorded (Table 3).

Altogether 22 species held territories in the plots. The average total density was 41 NT per 100 km2, five common species (Common Buzzard, Sparrowhawk, Tawny Owl, Ural Owl, Long-eared Owl) accounting for 69% of it. The rarest species – the Merlin and the Short-eared Owl – occurred in only one plot in one year.

Decline of the Goshawk was the only highly significant (P=0.004) difference between the average densities in the same plots in 1994-1998 and 1999-2003. The decline was on average 0.8±0.4 NT per 100 km2 or 34%. In ten years, the population has halved. Since also the productivity of the Goshawk has decreased, the most probable reason is the deterioration of habitats due to intensified forestry and/or abandonment of agricultural areas. There were also tendencies of decline in the Pygmy Owl (P=0.092) and of increase in the Marsh Harrier (P=0.070).

Most species had annually stable numbers, the only exception among common species being the Long-eared Owl. This species had regular three-year-period fluctuations of threefold amplitude, but the mean abundance has not changed since the late 1980s (Fig. 3). Top years of Long-eared Owl density (1990, 1993, 1996, 1999 and 2002) were good vole-years, which were also revealed in the productivities of several vole-eating species (the Common Buzzard, Lesser Spotted Eagle, Tawny, Ural and Long-eared Owls; see Fig. 4, Lõhmus 1999b and Lõhmus & Väli 2004).

Leito, A., Leito, T., Õunsaar, M. & Truu, J.

The numbers and distribution of the Eurasian Crane during autumn staging on Hiiumaa Island, and the impact of agriculture

Summary: Autumn staging of the Eurasian Crane (Grus grus) has been regularly monitored on Hiiumaa Island since 1982. The staging sites are mostly situated in the eastern and southern parts of the island. Particularly important sites are in the surroundings of Käina and Hellamaa villages (Figure 1). The main concentration areas of cranes have been stable but the relative importance of different staging sites has varied greatly between years (Table 1, Figure 2). Altogether, 960-4230 staging cranes have been censused on Hiiumaa Island in the autumns 1982-2002. The linear trend of numbers over the period suggests a decrease, though this is statistically not significant. The numbers of staging cranes depend on the structure and extent of field crop (Figure 4). We found statistically significant positive relationships between the number of cranes and the extent of winter wheat (Figure 5), winter rye and summer barley. The correlation between the crane numbers and the extent of winter wheat was strongest near Hellamaa (Figure 6). Significant negative correlations were found between the number of cranes and the extent of summer wheat and oats.

Ots, M. & Paal, U.

Rarities in Estonia 2001-2002: Report of the estonian Rarities Committee

Summary: This fourth report of the Estonian Rarities Committee covers the years 2001-2002, but some earlier records have also been included. Altogether 230 records were definitely assessed (Table 1), and 206 (90%) of these were accepted.

The records are listed in systematic order and presented chronologically. Records of birds of unclear origin, escapees from captivity, corrections and changes, records not accepted, and records formerly accepted but now rejected are listed separately from the main list of accepted records. The four numbers in brackets after species’ name (a/b – c/d) indicate (a) the total number of records before 2001, (b) the number of individuals (if possible to judge) before 2001; © the number of records in 2001-2002, (d) the number of individuals in 2001-2002. X instead of a number means unknown number of records or individuals. The details included for each record are: date(s), locality, parish (khk.), district, number of individuals (is., isend), pairs (paar), nests (pesa) etc. if more than one, sex and age (if known; a = calendar year) and names of observers. The meaning of some Estonian terms and expressions: ja = and, läh. = near, jv. = lake, s. = island, laht = bay, (tõenäoliselt) sama isend = (probably) the same individual, pesitsemine = breeding.

In 2001-2002, 5 new species in an apparently wild state (AERC category A) were added to the Estonian list: in 2001 Anas americana, Vanellus leucurus, Calidris acuminata and Lanius isabellinus, in 2002 Anthus godlewskii. At the same time, 2 species – Stercorarius skua and Luscinia megarhynchos – were excluded from the Estonian list because formerly accepted records were now rejected. In the same period, the breeding of Tringa stagnatilis and Hippolais caligata in Estonia was confirmed. Altogether, 344 species of apparently wild state or released species which have established self-supporting breeding populations in Estonia or in neighbouring countries (i.e. categories A-C) and five species of unclear origin (category D) have been recorded in Estonia by 31.12.2002.

Notes

Männik, R. & Sein, G. An Osprey nested successfully on an electricity pole in a white stork nest

Saks, L. A male Greenfinch with thirteen tail feathers

EOS chronicle and news

Elts, J., Kuresoo, A., Leibak, E., Leito, A., Lilleleht, V., Luigujõe, L., Lõhmus, A., Mägi, E. & Ots, M.

Status and numbers of Estonian birds, 1998-2002

PDF

Tuule, E. & Elts, J.

Numbers and population dynamics of the Magpie in the surroundings of Saue, 1963-1998

Summary: Breeding Magpies (Pica pica) were counted in an approximately 100 km2 area in the surroundings of Saue (near Tallinn), in 1963-1998. The landscape is mosaic and the share of open agricultural habitats has increased during the study years. The densities were estimated according to line transect counts on 50-m wide transects. In 1960-ties the Magpie was breeding mainly in scrubland, later the species spread to other biotopes, including human settlements (Figure 1, Table 1). Although the species continuously preferred scrubs, the share of this biotope as breeding place decreased: 84,7% of pairs bred here in 1960-ties, 64,4% in 1970-ties and 32,7% in 1990-ties. Total numbers have increased significantly, 30 pairs of Magpie bred in 60 km2 area in 1963, but about 480 pairs in 1990-ties. Most important reason for the increase is probably the favourable foraging conditions near human settlements and farms.

Lõhmus, A.

The Finnish method of line transects in the light of forest bird censuses in east central Estonia

Summary: The Finnish method of line transects (e.g. Järvinen et al. 1991) is among the main alternatives in estimating population sizes for common and widespread bird species in Estonia (see Ellermaa 2003a). The current paper draws attention to some problems of this method, as revealed by forest bird counts in Tartu county (east-central Estonia) on 30 randomly selected 2-km line transects in 2002-2003.

According to the protocol, a pair is recorded on the basis of a male or, when the male is not seen, then a female, a group of fledglings or a nest is also interpreted as a pair. However, in several well-defined cases, occurrence of one individual on the main belt does not show the occurrence of a pair there. Thus, single non-territorially behaving (foraging, flushed etc.) adult individuals of species with large home-ranges (e.g. Strix uralensis, Dryocopos martius) or non-consistent pairs (e.g. Scolopax rusticola) should rather be quantified as 0.5 pairs in their observation site. Similarly, independent of species, territorial individuals moving freely in and back over belt borders during observation should be assigned as 0.5 pairs to each relevant belt.

Next, I addressed the use of averaged correction coefficients for inclusion of distant observations, since the detectability of distant birds depends much on site and time. An alternative is to use wider but fixed-width survey belts. I compared bird numbers on the conventional 25+25 m main belt and on peripheral belts 25-50 m away. When species were ranked according to the share of distant observations, it appeared that a distinct species group (with less than 20% of pairs >50m away) had to be treated only on the basis of the main belt, whereas for other species, the peripheral belt was likely to increase precision due to larger sample much more than to lose accuracy due to missed pairs (Table 1). When compared with such fixed-width counts, the Finnish method seemed to systematically underestimate both mean densities (Table 3) and their precision (Fig. 2). The density underestimation was probably due to worse-than-average detectability of birds on forest land, indicating that correction coefficients may lead to results of unpredictable accuracy. At least twenty (not four, as proposed by Ellermaa 2003a) pairs on survey belt were needed to acquire meaningful confidence intervals (about half of the mean at 95% probability). I roughly calculated that mean densities of species with national populations less than 10 000 pairs can not be estimated reliably with transect counts in Estonia.

Väisänen, R. A. & Ellermaa, M.

Line transects should be sufficiently long: a comment to Lõhmus

Paal, U. & Väli, Ü.

Wintering of the Water Rail in Estonia

Summary: For clarifying the winter status of Water Rail (Rallus aquaticus) in Estonia, we gathered the records from literature, archives and internet, and added the personal observations. Based on these data we consider that the species winters here more often than is thought earlier and is probably the regular winterer in Estonia.

Notes

Aua, J.

Fledging of a brood of the Little Ringed Plover in August

Jürgens, M.

A breeding of the Red-breated Flycatcher in August

Elts, J. & Aua, J.

Woodcock’s rapid migration in autumn 2003

Anvelt, V.

A Hooded Crow participating in a fight between two White Storks

EOS chronicle and news

Lõhmus, A.

Is it possible to determine the occupying species and nest age from the dimensions of raptor nests?

Summary: Determining the occupying species and age of the nests of forest-dwelling raptors is important both in the conservation of threatened raptor species and raptor monitoring. This paper explores whether the relevant determination criteria could be simply derived from nest measurements, which can be easily taken by anyone able to climb the nests. The data were collected between 1991 and 2001 in a 900-km2 study area near Tartu, east-central Estonia. Three basic measurements (average diameter of nest and nest platform as well as nest depth; Fig. 1) were taken from more than 400 nests, representing six raptor species (Accipiter gentilis, A. nisus, Aquila clanga, A. pomarina, Buteo buteo, and Pernis apivorus). Although the average measurements differed significantly between the species (see Table 1 for the data of all nests and first-year nests), the ranges overlapped extensively. A discriminant analysis model failed to distinguish reliably between the species (Table 2), and I used an empirical approach to define the combinations of measurements, for which species determination was likely to be correct. In B. buteo, all three measurements increased with nest age (Fig. 2A), while in A. pomarina only nest depth increased (Fig. 2B). For these two species, linear regression models had a sufficient precision in estimating the nest age with an accuracy of ±1 yr up to 5 yr age (older nests were not further separated). In P. apivorus, nest dimensions did not change significantly with age. In general, nest dimensions were not a reliable criterion for conservation and monitoring purposes. Moreover, all the five larger species under consideration may switch to breed in a nest built by another species (at least two species nested in 15% of nests used for more than 2 yr; Table 3). Therefore, during forestry operations, large raptor nests and their immediate surroundings should be protected whenever possible.

Tuule, E., Tuule, A. & Elts, J.

Numbers and population dynamics of the Curlew in the surroundings of Saue, 1963-2002

Summary: Breeding Curlews (Numenius arquata) were counted in an approximately 100-km2 area in the surroundings of Saue (near Tallinn), 1963-2002. The landscape is mosaic and the share of open agricultural habitats has increased during the study years. The densities were estimated according to line transect counts on 50-m wide transects. The average annual density for the total area was 1.5 pairs/km2. The highest density was on meadows (3.7 p/km2), slightly less on pastures (2.4) and significantly smaller on arable fields (1.2) and woody and bushy meadows (0.7). The densities fluctuated most on pastures and were most stable on meadows. The total numbers of the species have been increased in the Saue area; among biotopes, the increases are reliable on arable fields and pastures.

Ellermaa, M.

The numbers of breeding bird populations in Pärnu county, 2000-2002

Summary: So far, the population estimates of Estonian breeding birds have been usually not based on standardized census methods and, hence, reliable data about abundancies of most species in larger regions are very scarce. We used the finnish line transect method to find out the sizes of breeding populations of about a hundred bird species in Pärnu county, SW Estonia (4800 km2). The results of the counts carried out 2000-2002 are compared with earlier estimates of breeding bird numbers in Pärnumaa.

Ellermaa, M.

Finnish line transect method

Summary: This paper is a methodological review of a powerful bird monitoring tool – the finnish line transect method (as described by Järvinen & Väisänen 1975) – and the possibilities of using it in Estonia. Correction coefficients for several Estonian breeding bird species, mostly derived from original material of the autor, are given in the Table 2. The English-speaking readers should consult the reference list for the details of the method.

Notes

Elts, J.

Variations in the results of Thrush Nightingale and Sedge Warbler counts

Aua, J.

Low breeding success in the Little Ringed Plover

EOS chronicle and news